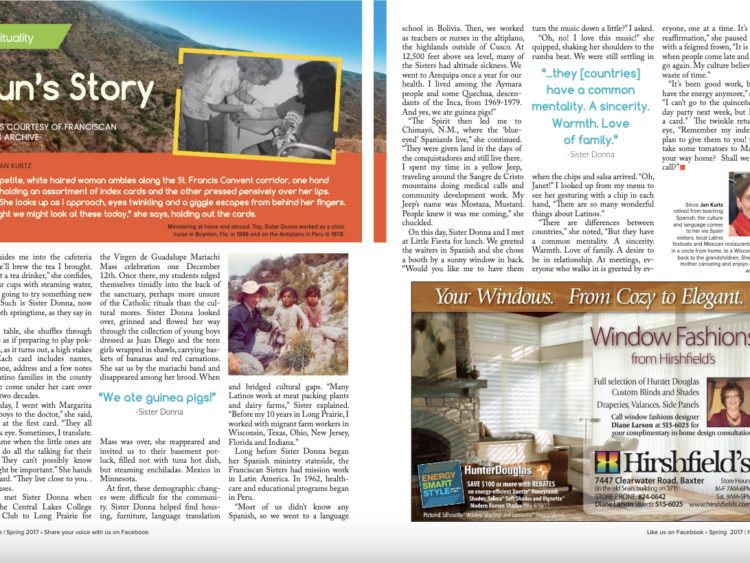

Nun’s Story in Her Voice Magazine Spring 2017

A petite, white haired woman ambles along the St. Francis Convent corridor, one hand holding an assortment of index cards and the other pressed pensively over her lips. She looks up as I approach, eyes twinkling and a giggle escapes from behind her fingers. “I thought we might look at these today,” she says, holding out the cards.

She guides me into the cafeteria where we’ll brew the tea I brought. “I am not a tea drinker,” she confides, filling our cups with steaming water, “But I’m going to try something new today!” Such is Sister Donna, now in her 86th springtime, as they say in Spanish.

She guides me into the cafeteria where we’ll brew the tea I brought. “I am not a tea drinker,” she confides, filling our cups with steaming water, “But I’m going to try something new today!” Such is Sister Donna, now in her 86th springtime, as they say in Spanish.

At the table, she shuffles through the cards as if preparing to play poker. This is, as it turns out, a high stakes game. Each card includes names, ages, phone, address and a few notes about Latino families in the county that have come under her care over the past two decades.

“Yesterday, I went with Margarita and her boys to the doctor,” she said, glancing at the first card. “They all have pink-eye. Sometimes, I translate. It’s a shame when the little ones are asked to do all the talking for their parents. They can’t possibly know what might be important.” She hands me the card. “They live close to you. . .” she pauses.

I first met Sister Donna when taking the Central Lakes College Spanish Club to Long Prairie for the Virgen de Guadalupe Mariachi Mass celebration one December 12th. Once there,

my students edged themselves timidly into the back of the sanctuary, perhaps more unsure of the Catholic rituals than the cultural mores. Sister Donna looked over, grinned and flowed her way through the collection of young boys dressed as Juan Diego and the teen girls wrapped in shawls, carrying baskets of bananas and red carnations. She sat us by the mariachi band and disappeared among her brood. When Mass was over, she reappeared and invited us to their basement potluck, filled not with tuna hot dish, but steaming enchiladas. Mexico in Minnesota!

At first, these demographic changes were difficult for the community. Sister Donna helped find housing, furniture, language translation and bridged cultural gaps. “Many Latinos work at meat packing plants and dairy farms,” Sister explained. “Before my ten years in Long Prairie, I worked with migrant farm workers in Wisconsin, Texas, Ohio, New Jersey, Florida and Indiana.”

Long before Sister Donna began her Spanish ministry stateside, the Fransiscan Sisters had mission work in Latin America. In 1962, health care and educational programs began in Peru.

“Most of us didn’t know any Spanish, so we went to a language school in Bolivia. Then, we worked as teachers or nurses in the altiplano, the highlands outside of Cusco. At 12,500 feet above sea level, many of the Sisters had altitude sickness. We went to Arequipa once a year for our health. I lived among the Aymara people and some Quechua, descendants of the Inca, from 1969-1979. And yes, we ate guinea pigs!”

“The Spirit then led me to Chimayó, New Mexico, where the ‘blue-eyed’ Spaniards live,” she continued. “They were given land in the days of the conquistadores and still live there. I spent my time in a yellow jeep, traveling around the Sangre de Cristo mountains doing medical calls and community development work. My jeep’s name was Mostaza, Mustard. People knew it was me coming,” she chuckled.

On this day, Sister Donna and I met at Little Fiesta for lunch. We greeted the waiters in Spanish and she choose a booth by a sunny window in back. “Would you like me to have them turn the music down a little?” I asked.

“Oh, no! I love this music!” she quipped, shaking her shoulders to the rumba beat. We were still settling in when the chips and salsa arrived. “Oh, Janet!” I looked up from my menu to see her gesturing with a chip in each hand, “There are so many wonderful things about Latinos.”

“There are differences between countries,” she noted, “But they have a common mentality. A sincerity. Warmth. Love of family. A desire to be in relationship. At meetings, everyone who walks in is greeted by everyone, one at a time. It’s a personal reaffirmation,” she paused and added with a feigned frown, “It is frustrating when people come late and around we go again. My culture believes that is a waste of time.”

“It’s been good work, but I don’t have the energy anymore,” she sighed. “I can’t go to the quinceñera’s birthday party next week, but I can send a card.”

“Remember my index cards?” the twinkle returns to her eye, “I plan to give them to you! Could you take some tomatoes to Margarita on your way home? Shall we give her a call?”