Unprecedented

Orientation included a walk from the outside world into a small entry room with 6” x 6” lock boxes for our telephones and car keys. A uniformed official passed the metal detector wand up one side and down the other before pressing the button, opening the door for our passage. The door clicked shut, locking us in. We were led along narrow corridors, passed interior windows that gave us a glimpse of rooms with one or two tables, some chairs and occasionally, into a larger area, locked beyond other portals.

“That is a classroom,” the officer pointed to the left, “And, that smaller room is where they meet with their lawyers.” He pushed a buzzer and we followed him down a yet smaller hallway, past a window marked library, and took seats around several short tables where we spent the next two hours watching a video on prison protocol.

Spanish is what brought me to this moment. A week earlier, one of the jail’s counselors sent an email to the college Spanish professor, seeking Spanish-speakers. She contacted me and we signed up for orientation together. Now, we were watching the required video, warning us not to touch inmates, no paper clips, and no offers to mail letters nor communicate with family members on the outside.

A week later, I accompanied another friend to her long-time class with the “regular” population which now included three Spanish-speakers. “They write in Spanish and I use Google translate to understand,” she explained, “but, it would be so much better to have someone to talk to them, to see how they are doing. I can’t imagine what this is like!”

After all the video’s warnings, I was unprepared to see her unload two bags and a suitcase full of books, papers, colored pencils and a device for music onto the table. The maximum of ten students filed in after being patted down and took seats, laughing, joking and eager to begin. These were the inmates, jailed for a variety of reasons and bonafide criminal charges.

The last three men, of smaller stature, perhaps in their 30s, entered quietly with their notebooks. I greeted them in Spanish. David from Ecuador. Alberto from Nicaragua. Lucio from Guatemala. They cautiously smiled. The other men nodded respectfully as we got acquainted. What was I allowed to ask? I needed to follow rules.

My thoughts returned to the first day in the jail lobby. While waiting for orientation, a smiling man burst into the room calling out, “Jan, it’s you! I’ve been trying to find you. We could use your help!” Standing before me was a former student of both my Spanish and Many Faces of Mexico classes! He led me into a side room and rapidly covered the newest part of his job as Jail Administrator – ICE detainees.

How could he best serve them? He got a call at 2:00 a.m. that more would arrive at 5:00. How long before they would be taken away again? Did they have lawyers? Families? Our eyes locked. We knew detainees were being rounded up by masked, bullet-proof vested, governmentally approved agents paid a $50,000 bonus, carrying military weapons. They were handcuffed in stores, outside churches, in parking lots and even daycare centers. Our county contracted with the federal government to hold them as part of the mass deportation process.

In the coming days, we cobbled together what seemed reasonable under unreasonable circumstances. I accompanied several officers to the large common area and began translating daily routines, behavioral expectations, use of tablets, daily showers, and finding out who had lawyers. Forty men from eight Latin American countries took their seats at the cafeteria tables. Freddie was bilingual and helped relay messages. On the far side of the room, half dozen Somalis translated for their countrymen. After an hour, the session was over, but I was asked to stay on, taking further questions and requests. The men flocked around me.

“Where are we? Can we contact our families? No, I don’t have my lawyer’s number. They took our phones. They made me sign a ‘self-deportation’ paper, so now what do I do? May I send a note to my wife? They are holding her here, too. How do I protect my children? They are with the neighbors. I just paid my lawyer $2600 for my final papers when they took me! How can my lawyer find me? Will I get the money back if I’m deported? I can’t read these papers. They took my glasses. I have gastritis problems. What can I do to eat? I can’t sleep with the lights on all the time.”

Someone handed me a page with a dozen names wanting to self-deport. “We can pay ourselves! We want to leave!” Yet, I was the only one free to leave that day.

When I returned with a bag of “cheater” glasses, Pedro had already been taken away. A special diet was ordered and the man with gastritis patted his stomach and nodded that he was fine. Eye-covers were available for purchase at the kiosk. Do they have money in their accounts? Lawyers were contacted. Zoom meetings might be possible. The Chilean pastor was given permission to hold a service, if I was in the room. I translated for two D.O.P.A. (Delegation of Parental Authority) documents to protect children from foster care arrangements. I signed up with the Programs people to offer English and Crafts, but continuity is impossible as “students” are whisked away without notice.

A month later, David, Alberto and Lucio are still with me. They ask why I pronounce the “t” in “Saturday” with a “d” sound. Cristobal finishes his yarn art Ecuadorian Star and said he’d like to put his three-year-old son’s picture in the center. Sandy, a Venezuelan, puts his hands into the prayer position as he thanks me on his way back into lockdown. I put my hands to my heart and bowed as the door closed and locked between us.

That night, as Sandy slept a small-town jail in Minnesota, the United States of America invaded his country, taking his President and the president’s wife to New York for trial.

Un – president – ed???

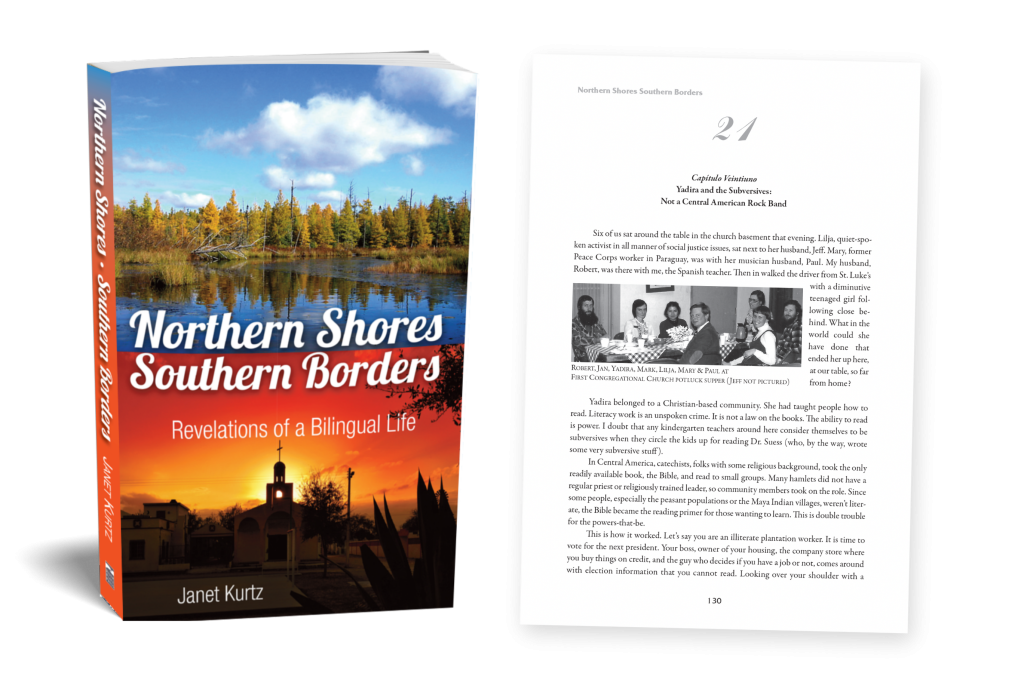

In my book, Northern Shores/Southern Borders, Chapter 23, p. 135, titled Coffee and Bananas, and Chapter 24: p. 138, Who Are the Terrorists? You will find the fast track on the history that brought us to this day.

Other recommended readings:

Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala

Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America

Oh Jan,

Thank you so much for the work you are doing and for this glimpse into the jail. We are all human….

Thanks Jan for giving us a very real “ day in the life of “ during this very unreal time. I know people who only use Fox “ news “ as their source for information and have a very different view of what’s happening. During the invasion of LA a woman I am acquainted with told me it was a hellhole and war zone before Trump sent in troops. Thankfully I know someone who lives in the heart of that area of LA and I gave this woman a very different account of what it was like living there. It at least made her think for a moment about the “ information “ she received.

Thank you for your work and your heart. I love the stars ! Why do we pronounce the “t” in Saturday like a “d” ? ; )