Mascaras: Mexican Masks – Then and Now

Patzcuaro, Mexico, early morning. Debora, our local guide, rounded us up in the patio of La Mansión de los Sueños, a former colonial edifice that had served as a sumptuous home for a wealthy family in the day. Our group of fifteen travelers, enrolled in Spanish classes, visits to the Rosario Butterfly reserve, and Mexican artisan excursions, collected in the center courtyard, a jungle of tropical plants, stone carved benches and splashing fountains.

“I have a special event for you today,” Deborah began with a twinkle in her eye. “Not only will we meet the Master Mask maker of Mexico, but Felipe Horta’s premier mask will be worn in the village ceremony while we are visiting.”

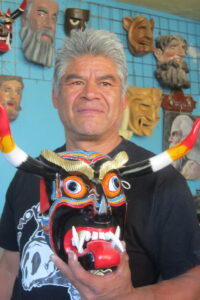

Felipe Horta – Master Mask Maker of Purepecha tradition

Looking back at that visit, I regret not having done my homework on Señor Horta, his masks and his village of Tócuaro. For thirty years, he has continued the family artwork, specializing in the traditional Purepecha masks. His masks have traveled into innumerable tourist homes, but more notably, into museums around the world, including the Vatican itself.

The first mask in the Americas, a fossilized llama vertebrae in the shape of a coyote’s head circa 10,000 – 12,000 B.C., was discovered in the area of Tequixquiac, Mexico. Over the centuries, indigenous groups congregated in clans, tribes and later, into masterful civilizations, all of which implemented masks in some format.

The Olmecs, perhaps the “Mother Culture” of Mexican indigenous, created masks of jade, a stone they related to fertility. Images of jaguars carried on the creation story of the jaguar woman in their culture in the area of Veracruz.

The Aztecs created death masks or carved images of their gods. Priests wore masks during the religious ritual of human sacrifice, performed to please the Sun God, insuring its return each day. Their warriors wore masks that terrorized the enemy on the battle field.

Masks transformed the wearer into a new being, taking on stronger powers, mythical creatures. Masks were essential to dance. The deer dance, recreating a hunt, includes a deer masked man, leaping through the woods before the hunters.

Los Viejitos, The Little Old Men dance, is performed by young boys wearing masks with craggy noses, deep wrinkles and mischievous grins. They lean heavily on their canes, put a hand to their “aching” lower backs, shuffle around, flirting with pretty girls and sometimes tripping on their own walking sticks, to the delight of the audiences.

Los Viejitos dancers at Long Prairie, MN

5 de mayo celebration

Masks of devils were introduced with the arrival of the Spaniards and their religious beliefs of heaven and hell. The idea of hell was unknown in the Americas, but now entered their collective conscious through dances depicting good and evil, conflict, and frankly, fear – an effective tool of conversion.

Now, catapult yourself to 2020 and the new use of the mask in the Americas. From a religious icon, to a representation of power, symbolic dances and mystical powers of character transformation, the mask has landed in the center of a debated, politicized hot spot topic. To wear or not to wear a mask, that is the question. (Apologizes to Shakespeare)

When science suggested I wear a mask to grocery shop, inside buildings, or in larger group gatherings, I complied. I also stop at stop signs, go in the door marked “Enter”, don’t drink out of bottles with a “Mr. Yuck” sticker, and stand on the spot marked “six feet” to keep the prescribed distance from the next person in line. Wearing a mask might help our country’s fight against an airborne virus. Even if one does not believe that, what harm can come from giving masks a chance?

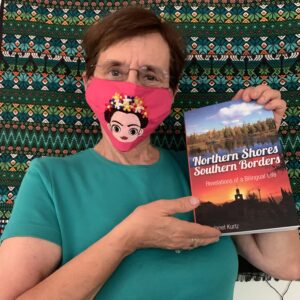

Like cultures of the past, masks symbolize something. This time, it symbolizes an effort to slow a disease, a communal effort to keep everyone healthy. I did not want to take from the mask supply needed by health workers, so gratefully accepted various renditions for talented neighbors and family members. Until. . .

. . . a FaceBook share introduced me to Lolo Mercadito and their Mexican artesano masks! There, before my eyes, masks fashioned by artisans representing their cultural heritage paraded before my eyes! Over time, indigenous art has morphed from the daily use of its mother culture into items more readily used in the culture to which it is being sold. For example, the Guatemala’s Mayan embroidered huipil blouse became purses and wall hangings for tourist consumption. Now, the embroidery symbols, the colors and even Frida, are being incorporated into masks!

What a concept! A teaching moment. A new perspective. Image a grocery store filled with people wearing culture! A chance to share.

“Why yes, thanks for asking. That is Frida Kahlo, an amazing feminist artist of the 20th century.”

“This design? It’s from the Puebla culture. Their civilization inhabited south central Mexico long before Columbus.”

Or, the Otomí or Oaxacan or. . . the Packers or the Vikings! Did you know you can identify entire civilizations by their colors and symbols? Societies have been identified this way for millennia.

A mask. A symbol. A representation of who you are, maybe only for the moments that you wear it. A thing of transformation, and now, a request to come together for the well-being of everyone – the greater good. “We all do better when we all are doing better.”

What will your symbol look like? How can you personalize your message? Let’s literally “put on a new face” and spread culture, not viruses. Regardless of what you believe in this pandemic, the wearing of masks is part of human history. Look at it as an opportunity to share an inner belief, a love of art, a sign of culture, your message. . . until we meet again and see each other’s smiles.

Jan selling her “Book Baby” with Frida Mask

Culture “En Vivo” Felipe Horta explains his work and the Pastorela tradition:

And now, Los Viejitos: